“Tibetans discern six ‘betweens’: the intervals between birth and death (‘life between’) sleep and waking (‘dream between’) waking and trance (‘trance between’) and three betweens during the death-rebirth process (‘death-point’, ‘reality’, and ‘existence betweens’).”

Robert A. Thurman introducing his translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, otherwise known as The Great Book of Liberation Through Understanding In The Between

About five years ago, I spent some time studying dream theories and the science of sleep for a book that I was writing. No matter how much I read, two questions remained unanswered. The first was one that I had naively expected to find concluded by science: What are dreams? And the second was something I have ruminated on since the recurring nightmares and lucid dreams that filled my childhood: Why do dreams bend time?

I did not expect that it would be in my meditation practice where I would begin to form answers to both these questions. Nor did I expect that in turn, by trying to understand my mind’s behaviour while asleep, I would find a new understanding of my mind’s behaviour while awake, and gain insight into the nature and experience of time itself.

I hope that in the process of outlining a suggestion of what our dreams might be, and of why time behaves strangely when we sleep, I can also demystify meditation. What a lofty word meditation is, laden with expectation, loaded with a weight of spiritual imagery: nirvana, Buddha, Zen, samadhi, calm, lotus position, an empty mind. Its truth is far simpler and more accessible; it is a more real and practical pursuit than is implied by any of the ethereal shimmer that often surrounds our perception of it. More than this though, I hope that I can introduce time spent in silence with our Self, as an important and useful tool for complete living.

Dream Theory & Dream Time

I am sure you are familiar with some of the most prominent dream theories: Freud suggested that the world of sleep is a comfortable padded cell where our innermost desires can play themselves out; There is a mental housekeeping theory, that the problems we are pondering in waking life – and the memories that trouble us – are processed more effectively by the brain in the wild, unboundaried landscape of our dreams; There is an idea that dreams are an imaginative response to external stimuli, such as a hot room, a feeling of nausea, or a noisy alarm clock.

Matthew Walker’s incredible book Why We Sleep describes how a lack of the REM sleep that breeds the majority of our dreams, can damage our memory and cognition. He also describes how people who successfully recover from trauma tend to report dreaming repeatedly about their experiences, while people who go on to suffer from PTSD often experience a notable lack of dreams. It does seem then, that there is a therapeutic, cathartic, sorting process that is taking place while we sleep – a brightly-coloured loopy filing cabinet of wonky thoughts that we can categorise and pore over after dark, when nobody else is looking.

During my reading, I came across the activation-synthesis theory, proposed by J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley in 1977. It describes dreams as circuits in the brain that become activated in REM sleep. Freed from the relentless stimulation of waking life, the limbic system within the brain creates an array of electrical impulses that we synthesize and interpret when we wake up searching for meaning; our dreams are waking hindsight interpretations of random nocturnal neurology.

It seems a shame to reduce our magical night-time adventures to meaningless sparks of electrical activity, but that’s not quite what Hobson is saying. He suggests that dreaming is in fact “our most creative conscious state, one in which the chaotic, spontaneous recombination of cognitive elements produces novel configurations or information: new ideas.” Sleep illuminates the incessant thought loops that form the backdrop of our mental landscape; they are always happening, but come to the foreground at night when other parts of our brain and body take rest.

As well as the purpose and significance of dreams, I wanted to understand the strange way that time seems to bend in our sleep. I have always been fascinated by the idea of time as a measurable concept, and the way in which it is uniquely described by different cultures. There is a disconnect that I’m sure we all experience, between the methodical order of the second, minutes, and hours of the clock, and the inconsistent and subjective way that time actually feels. The British Museum has a room dedicated to exploring how ancient Egypt and other cultures have tracked and measured the passing of time. I used to go there regularly while at university (in between all the mad parties obviously), exploring how the actual language and systems that our country/tribe/species uses to describe time, profoundly impact how time is felt and understood.

Does your culture arrange time along a line, for example, with ‘past’ to the left and ‘future’ to the right? This linear, ‘Western’ approach is one we probably recognise. Does your culture arrange time on a circle, an ever-turning loop of repeated cycles mirroring the seasons, the moon, death and rebirth – such as the Buddhist Dharma Wheel, or the Mesoamerican Calendar Round? Or does your culture exist linguistically free from time, like some of the Amazon tribes that have been found to contain no language to describe ageing, the passing of time, or to define time itself as a concept?

You don’t have to compare cultures, tribes, and societies though, to find inconsistencies in the experience of time: time shape-shifts even inside our own heads. I find the narrative thread of a dream to be a slippery beast, something you may notice if you ever attempt to write a dream down, or to describe it accurately to another person. I often wake up with a vivid memory that feels crystal clear for as long as it is locked inside my head, but disintegrates into nonsense fragments as soon as I try to explain it using words.

Studies of the brain during REM sleep suggest that dreams can last from a few seconds to half an hour, but I find it odd that I can never pinpoint for myself how long a dream has lasted. Something that I remember as a split-second vision stretches and elongates in the retelling, as I discover its backstory and context – a huge and detailed weight of information that I suddenly realise was a part of the dream, though it was never exactly explained. Entire lives and relationships, layers and nuance, are bunched up inside a few indeterminate minutes or seconds of REM.

It is this strange dissolving and expanding of time that I began to see a mirror of in my meditation practice.

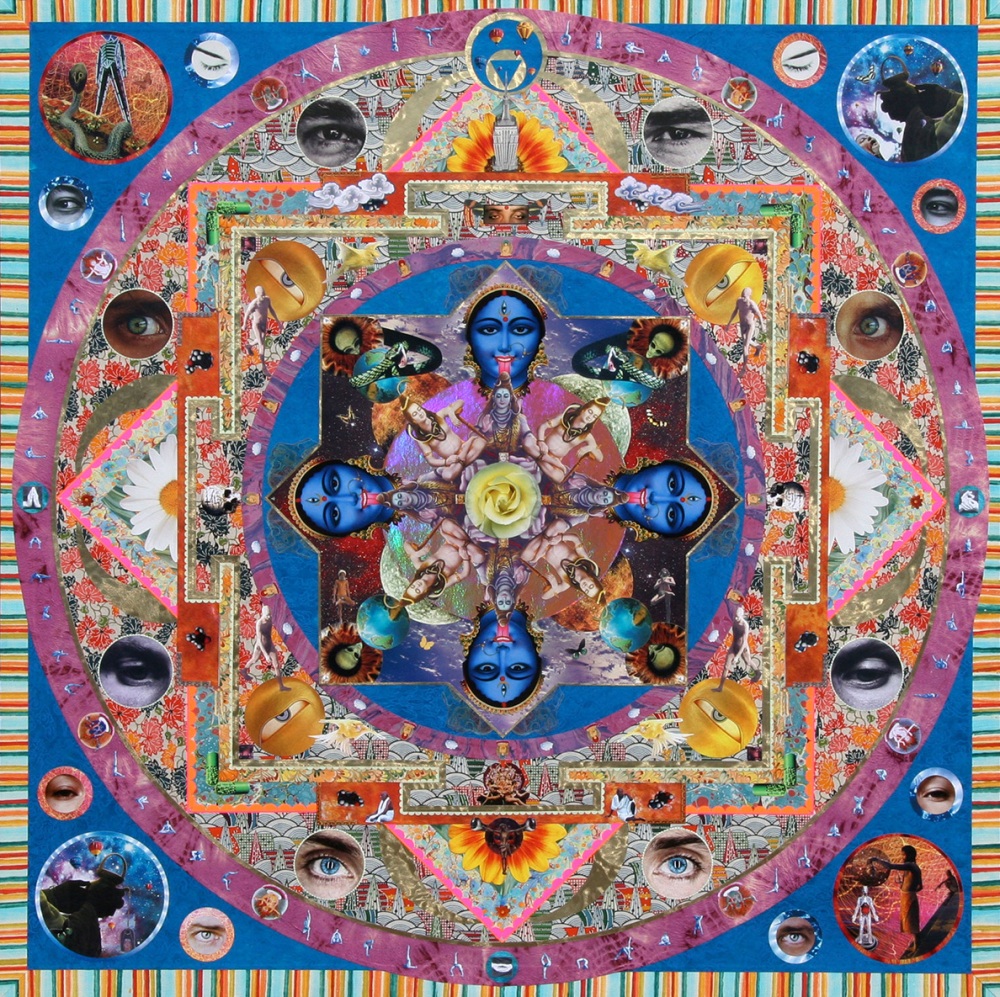

Mandala by Sebastian Wahl

Thought Loops in Meditation

You are probably familiar with breath awareness meditation. It is a lovely simple tool for cultivating presence, quiet, and coming into (often tricky and sticky) relationship with yourself. Using this technique, I sit or lie and observe the breath coming in to my body with each inhale and leaving it with each exhale. As I breathe in, I say silently breathing in and as I breathe out I say silently breathing out. As thoughts begin to line up inside my head, instead of thinking them or getting carried away on their current, I observe them as separate from me, a river of water flowing past, and say silently thinking before allowing the thought to recede over the horizon of my mind, and coming back to an awareness of the breath.

Over time it occurred to me that these thoughts have a similar relationship to time as dreams do. In the stillness of meditation, a thought will often flicker into being and fade away in the time it takes me to say silently thinking. In ‘real’ time, or Clock Time, then: a second. Yet within that tiny second-long thought loop an entire world has shimmered into existence inside my mind, and what’s more, my brain has been able to process and form an opinion on that entire world within that single second, almost as though it is operating on two different time zones at once.

For example, let’s say I am meditating early one morning before work. It is 6am. Later that day I am giving a pitch at work where I will present a film idea to some prospective clients. I work for a small start-up company that I love, and I desperately want to win the job for them. Sitting in silence, observing my breath, I realise that I have begun to imagine the pitch, anticipating how it might play out. I say thinking silently in my head, and allow the thought to pass and fade away. It takes around two seconds. In those two seconds though, I have conjured up and had time to consider and feel: the location, the content of the pitch and the script I have written, the people who will be there and the history of my relationship with – and opinion of – each one of them, as well as how those dynamics will come to bear on that particular moment, how I feel about the project, my concerns for my ability to win the pitch and for my company’s ability to survive if I don’t, my relationship with my boss and our history of working together and how I feel about those things, what I am wearing (well, duh) and how I feel about my body that day, how I feel standing that body up in front of a room full of people. I haven’t thought any of this in words, but I have felt all of it: it is all there, within that single thought. Phew. That’s a hell of a lot of stuff to cram into the time it takes to say thinking. Thoughts are like a tardis, a detailed diorama piled up on top of itself inside a flash of daylight time.

Thought Time seems to run on a different track from Clock Time. A thought loop that takes a second to experience, lasts many times longer in its explaining. Thought Time is the time zone of the waking mind, the scrunched up, bunched up palimpsest of feelings that swirl and loop and dart to a million places as a second of Clock Time creeps by. I am sure many of you would describe yourself as ‘over-thinkers’ – I certainly would. I think that this is because regular thinking feels like overthinking. It moves at such an accelerated, elevated pace, fitting an exhausting weight of mind stuff into a tiny portion of Clock Time.

In this discovery of multiple time zones, lies an answer to why time bends in that subjective, fluid way for all of us, as we sway from the methodical tick-tock of the clock, to the whirring engine of thought. In meditation, I often find myself in a corridor between the two, an in-between space where the two time zones of Thought and Clock meet one another and coalesce, where I can see and feel both simultaneously.

Thought Loops in the Dream Between

The speed of thoughts, and the way they last a second but contain an entire world, reminded me of Dream Time. Waking up with a clear memory of a dream hanging in the air around me, I often realise that its series of visions contained a level of understanding, or dream context, that informed the meaning of everything I saw. This context was never explained in the dream itself: it was just something I knew. In its explanation, the dream vision begins to morph and elongate, taking up more space and time to speak, than it ever took to experience.

Recently, I dreamt of two crystal clear moments: at first, I was on a beach with my brother and another man; then I was swimming out to sea from a little cove. But there was also a weight of context and understanding that existed in both of these moments: Me and my brother were on a beach in Bali chatting to one of his old friends from school (once I had woken up I realised that this third person was a stranger, and not somebody I’d ever seen before; in the dream he was my brother’s school friend). My brother and his friend lived in the next cove over from me, and they had come to visit. A girl was going to go and meet my brother’s friend later because they were going on a date. We were giving him some advice and telling him to take her out for dinner. None of this was explained in the dream – it was just unspoken fact. All I actually saw was the three of us chatting on the beach. The sea was really rough and there were huge stingrays in the water. We were worried that the girl was going to swim to the wrong cove and get injured by the stingrays. We decided to swim out around the stingrays, find her and bring her in to the right cove where he lived. Again, all I dreamt was a snapshot clip of myself in the rough water – everything that had led up to the moment already existed inside my dreaming head, in the same way that when you wake up in the morning you understand who you are, where you are, and what that place means to you.

When my daughter was five months old, I suffered from about six weeks of crippling postnatal insomnia. I can honestly say it is one of the worst things I’ve ever experienced, and there were times when I actually worried (drama queen alert) that I might die. Four sleepless nights in labour, followed by the torture chamber of being woken up every couple of hours for weeks on end, and my ability to fall asleep got broken and disappeared. I couldn’t stand that I was never in control of when I would next get woken up, and because I was always mentally preparing to ‘switch back on’ at a moment’s notice, my brain gave up bothering to switch itself off in the first place.

I became obsessed with the process of falling asleep. Something we usually have to do once or twice in a twenty-four-hour period, a new mum has to remember how to do over and over again. What is falling asleep? How did I used to it? Is this it now? Am I falling asleep now? Oh my god I am! I’m actually going to fall asleep! How wonderfu- oh, I’ve woken myself up in excitement. At the time, allowing my brain to drop from being awake to being not awake, was such a fragile process that I would often accidentally look directly at it, and watch what happened to my thoughts as they slid closer to that dividing line.

If meditation is the corridor between Clock and Thought Time, falling asleep is the corridor between Clock and Dream Time. But it wasn’t just Clock Time turning into Dream Time that I saw as I tipped forward over the edge: it was my thoughts turning into dreams. The high-speed spirals of my waking mind would begin to pull themselves apart, disjoint, bend and merge with one another. As I slipped towards sleep, I would realise that I didn’t know why or how I was thinking a certain thing. I’d wonder how I’d got there, and try and retrace my thought thread, but everything was dismembered, the gap between images too big to make connections. Sometimes I would realise I was in between waking and sleeping, because my thoughts were loopy, nonsensical and weird. It was like using my daytime brain to look at my night-time brain from the outside, as the tightly wound coils of a waking thought loop loosened their grip on reality, dancing and swaying in the dream breeze. I was in between waking and sleeping, but I was also in between thinking and dreaming.

For now, this is my answer to the question What are dreams? I think it is likely that dreams are very similar to the constant thought spirals of the waking mind. They are the loopy, sleepy cousins of thought. Just as the mind’s thinking often accelerates when we first sit still in meditation and slow the rest of our experience down, so dreams become illuminated as the mind floats away across a sea of sleep waves. Where thoughts are ‘thought’, dreams are felt. Analysis falls away, randomness rules, wonky connections and swirling combinations appear. Dream Time is faster than Clock Time, but it is less ordered than Thought Time. It meanders, takes the scenic route, sometimes goes backwards, doing loop the loops, picking things up along the way. Why do dreams bend time? They don’t exactly, they just exist on their own time zone, shimmering within the portals they open up inside a few seconds of Clock Time.

Unifying the Time Zones through Meditation

योगश्चित्तवृत्तिनिरोधः ॥२॥

yogaś-citta-vr̥tti-nirodhaḥ ॥2॥

Yoga is the stilling of the fluctuations of the mind.

As I started to understand my dreams better, I started to understand meditation better. I began to observe its ability to unify the conflicting time zones that we oscillate between, bringing the speed of the thinking mind closer towards the comparative stillness of the clock, and occasionally beyond to a lamentably fleeting state of utter timelessness and freedom.

The often-quoted second sutra from Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras describes yoga as “the stilling of the fluctuations of the mind.” While the physical poses that we see now in modern postural yoga have emerged over the last nine hundred years or so, when Patanjali’s sutra was recorded around 2000 BCE, yoga asana or posture was generally considered to be a steady and comfortable seat. Yoga as an activity then, more closely resembled what we now consider seated meditation.

Stilling the fluctuations or thought loops of the mind, takes us out of our high-speed interior time zone, into the relative quiet of the now. Something we hear spoken about a lot at the moment is ‘presence’ – our ability to establish ourselves in the present moment. The present moment is medicine for a mind enslaved to the speed of thoughts. The wonderful spiritual leader Thich Nhat Hanh describes how human beings are that rare thing: an alive being that knows it is alive. The present moment is the only place in which this miracle is true. In our thoughts we are reliving the past and anticipating the future; it is only in the present moment that we simply are, a being with aliveness running through our body from top to toe.

If you are aware of how incessantly and automatically the mind thinks, a state of true presence and stillness may feel like an impossible goal. I use the word ‘goal’ deliberately: meditation does have a goal. I often hear the yogic teaching of aparigraha or non-attachment described as though our practice is a place where we should be free from striving, free from goals, consumed by the journey not the destination. But you cannot practice non-attachment to nothingness. When you consider how many thousands of mind fluctuations, or thought loops, inhabit our mental landscape over the course of a few seconds, I would suggest that finding stillness of the mind is a pretty huge goal.

The fact that meditation does have an ultimate goal, or a state that we are aiming for, is where the true power of the practice lies. If it were simply about checking out, switching off, and letting go, it would not equip us so exquisitely for navigating the human condition. We are consciously alive; We have thoughts; We want things. The delicate and fragile state of mental stillness, only exists if you don’t reach for it – just as the delicate and fragile state of falling asleep evaporates into wakefulness if you try too hard. In practising new and softer ways of positioning ourselves and our egos in relation to the things we desire, we may discover that while that thing we want is over there, where we are sitting now is a beautiful place. And if we pay enough attention to this beautiful place, its detail may consume us with a focus that lifts us up, briefly, on the levity of not wanting. That is non-attachment.

Meditation is not an entirely goal-free space, but nor is it a thought-free space. We will not find a state of not-wanting, by wanting not to think. When we are in conflict with our thoughts, we tend to have many more of them. We might think a thought, then think the opposing thought, then think some other options for the opposing thought, then berate ourselves for worrying about the thought, and then think the thought again. If we simply notice the thought, then there are just two things: the Thought, and the Noticing. Instead of viewing meditation as trying not to have thoughts, it would be more accurate to view it as simply being aware of our thoughts, as opposed to being them. If we notice that we are thinking, in a way we are already meditating. Noticing our thoughts is a state of metacognition- thinking about thinking – and by noticing them, we divide the part of ourselves that witnesses the thought, from the thought itself.

In separating the Thought from the Noticing, we connect and root down into an enduring, eternal stillness, a time zone far slower than Thought Time, and even slower than Clock Time. We come into relationship with the Time of the Self: the real you, the person who is watching your thoughts, the boulder in the middle of the stream that water flows past, the clear blue sky that weather passes across. This observer, Self, soul, is a still totem standing silently amidst the swirling spirals of our relentless thinking.

Meditation is an oscillation between these time zones, as we bounce back and forth between Thought Time and Clock Time, occasionally glimpsing the eternal Self. I think one of the barriers to maintaining a meditation practice, is the fact that this natural oscillation often feels as though we are trying and failing. We give up, because we keep having thoughts. More often than not, for me at least, it feels like an ‘unsuccessful’ practice. But this is where the texture of meditation sits outside the texture of daily life: it is not about success or failure, and while it may have a ‘goal’, that goal does not exist in the linear, absolute way we are accustomed to. It is not something that can be permanently achieved; it does not have an ending or finished state. Meditation is the act of loosening the white-knuckle grip on our thoughts, until over time we become more adept at cultivating space between loose fingers, and eventually allowing some of that heavy grey matter to float away on the wind. But it doesn’t happen cleanly or perfectly; our mind eases and constricts, relaxes and tenses. What is practice anyway, but a repeated attempt?

Martian Marble by Sebatian Wahl

Truth in the Between

My corridors between time zones were identified under a different name by Tibetan spiritualists as far back as the 8th century, when the Tibetan Book of the Dead was composed by Padmasambhava. A more accurate translation of its original title Bardo Thodol is ‘The Great Book of Liberation through Understanding in the Between’. The word bardo is understood to mean a ‘between place’ or ‘intermediate state’, and the Tibetans identified six of these between places: between birth and death (‘life between’), sleep and waking (‘dream between’), waking and trance (‘trance between’), and three betweens during the death-rebirth process (‘death-point’, ‘reality’, and ‘existence betweens’). By fostering an awareness of these in-between places, and spending time consciously inhabiting them, Tibetans found clarity on how to navigate the largest and most complex of them all: the great divide between death and rebirth, before emerging into new life a little closer to enlightenment. To be gifted the chance to spend your ‘life between’ inhabiting human form, was to be given the sentience and conscious thought required to explore the fabric of existence, to seed good karma and spread positive energy; to spend a human life in ignorance or unkindness was to squander the potential for ultimate liberation.

There is a simple truth in these in-between places, and in the weightless, rootless sensation of passing from one state to another with complete awareness. In meditation, we become conscious of two additional between places or intermediate states: ‘breath between’ and ‘breathless between’. In ‘breath between’ we hover in a state of fullness, sitting at the top of an inhale, we pause before the cycle of air tumbles down the descending curve of its circle, and into an exhale breath. In ‘breathless between’ we sink temporarily into an empty, breathless state, waiting for the catch and lift of the inhale, as the air around us pushes itself down into our lungs. Pranayama (yogic breathwork) labels these between places stambha or ‘suspension’; these two foundational intermediate states are the simplest and most available for contemplation.

These in-betweens are reflections of the fact that we are never quite one thing or the other. As human beings, we are at risk of always searching for certainty, oneness, a destination, a singular state or experience. By paying close attention to the fabric of experienced reality, from the macro view of our very life as a suspension between two things – rebirth and death – to the micro view of the tiny ceaseless pause and release of our breathing, we discover that yearning after neat, ordered certainty, or permanence, is a futile desire.

Earlier I mentioned the uncomfortable oscillation of meditation, as we bounce around between time zones, between thinking and being free from thought. This discomfort exists in part because it shows us our truth. Even the very Clock Time that I have been describing, is not quite one thing or another: it is a dual thing, at once linear and circular. Each second, minute, hour, day, week, month advances us through linear time, propelling us forward through calendar years, centuries and into the future. Yet each cycle of the clock is an identical circle, sixty seconds repeated; sixty minutes repeated; twenty-four hours repeated; seven days repeated; twelve months repeated; four seasons repeated, while simultaneously always only ever being ‘now’. We cling relentlessly to singularity, when almost everything about being alive is a tangled mass of shimmering multiplicity. Even the way Patanjali’s sutra is written is a clue, a glimpse of a never-finished, constantly moving universal energy. ‘Yoga is the stilling of the fluctuations of the mind’. It is not ‘a still mind without fluctuations’: it is a constant process. And yet, in noticing these fluctuations, in accepting impermanence, in allowing multiplicity, we connect with the eternal Self and find ourselves, paradoxically, in stillness.

A Lineage of Soul Cartographers

It is incredibly exciting to me, that human beings separated by thousands of years, many hundreds of miles, disjointed by different cultures and languages, can arrive at similar conclusions simply by spending time in contemplation of how it feels to be alive – from the Tibetan spiritualists of the 8th century, to little me on my yoga mat, and many thousands of people in between.

Recently I have watched as science has validated many aspects of yoga and meditation; star-studded ancestral ground re-trodden with the familiar footprints of logic. Each time I see a new aspect of my practice ‘proven’, I feel a jolt of excitement, closely followed by a squirm of discomfort. Do I value these practices more once they have science’s backing? In matters of felt human experience, what should be more important: data-driven evidence carried out in a controlled way and using the respected language of science, or my own embodied experience of practices that clearly benefit my life?

Since I first began my yoga practice it has been clear to me that the foundation of its potency lies within the breath. I have found myself, along with millions of other daily practitioners, learning how to sustain nasal breathing, then learning how to sustain ujjayi breathing, and recently finding that the breath naturally falls away, becoming almost invisible in its gentleness, even in the intense heat of a strong practice. Neuroscience now understands that the soft nasal breathing taught in yoga, and the emphasis on a long slow exhale, is an effective tool for engaging the parasympathetic nervous system – our restorative, rest and digest wiring. This deep and intelligent healing system of the body allows our immune system to restore and reboot, and our digestive system to work uninterrupted by the periodic injections of adrenaline (or caffeine) that we are so used to consuming as fuel.

More than just soft nasal breathing though, there are specific yogic practices that neuroscience now believes stimulate the vagus nerve, the foundation of the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS). In Eddie Stern’s latest book (One Simple Thing: A New Look at the Science of Yoga and How it can Transform your Life) he discusses how the application of gentle pressure to the ‘third eye centre’ – a spot just above and in between your eyebrows – stimulates the vagus nerve, and helps us drop into a more relaxed state. As well as the third eye centre relating to the PSNS, so too does the throat: the oceanic wavelike sound of ujjayi breathing, found by pulling air through a lightly constricted throat while simultaneously opening the soft palette slightly at the back of the mouth, is also now believed to stimulate the vagus nerve. In addition to these individual points of connection, we now know that it is possible to ‘tone’ our vagus nerve, strengthening its web of connections by the repeated practice of consciously dropping into rest.

That gentle, constant, almost invisible nasal breath that I eventually arrived at after almost a decade of daily practice, is at the centre of a deep and restorative pranayama practice, but also now at the centre of a recent book The Oxygen Advantage, in which Patrick McKeown threads together multiple studies of nasal breathing and its effects on athletic performance and overall health. It is not just nasal breathing that McKeown is interested in; it is incredibly light nasal breathing, almost to the point of air hunger. McKeown explains that although there is little variability from person to person in terms of the oxygen saturation of our blood, there is often great variability in the efficiency with which our blood cells deliver this oxygen to the rest of our body. It is the level of carbon dioxide in our blood that catalyses this oxygen offload, and we must breathe gently enough and not ‘over breathe’ to ensure we have high enough levels of CO2 present to create efficient oxygenation. Conversely then, it is not big deep breaths that will oxygenate our body more thoroughly, but learning to breathe a bit less and develop tolerance to higher levels of CO2.

Getting more specific still, the practice of humming that is taught in brahmari breath, or in the resonant end to the chant of ‘Om’, is now understood to cause a release of nitric oxide in the nasal cavity. In an article published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, Drs Weitsberg and Lundberg described how humming releases up to fifteen times more nitric oxide than a normal exhalation. The relationship between sound and nitric oxide has been found to exist even when the cells affected by the sound are isolated in a petri dish; Dr John Beaulieu has demonstrated that these isolated cells will release nitric oxide when placed near the sound waves of a tuning fork. This short-lived gas dilates the air passages in our lungs as well as our blood vessels, lowering blood pressure. Nitric oxide also plays an important role in homeostasis, neurotransmission, immune defence and respiration.

In discussing these findings, McKeown references the parallels between ancient felt truth, and contemporary evidential proof: ‘The breathwork technique…Brahmari involves…humming on each exhalation to generate a sound similar to a bee buzzing, and while the exact science may have been a mystery to the creators of this meditation method, the associated feeling of calmness of the mind is a clear indication of its benefit’. I may be imposing an invisible tone of voice on McKeown’s writing (based on my own involuntary reactions) but I sense that ‘the exact science’ feels like a necessary validation for him – and no doubt for many of us – giving a reassuring value to the practice; proving the method in a manner we understand.

These are just a few choice examples of parallels between ancient yoga and modern science; there are many, many more. I admit to taking comfort in the fact that science accommodates practices that are often viewed as sitting outside its framework. My analytical, evidence-hungry brain does find a new weight of validity to aspects of my daily practice once I understand why they are effective. But the nature of a watertight scientific experiment is that it must consider an extremely narrow point of focus in order to exercise correct control over one single variable. Science moves in tiny increments through larger subjects, and it is important to remember that its wider lens is therefore made up of a series of tiny views; an image of the world that up close is revealed as hundreds of smaller images, or pixels. It is important to be open to the possibility that there are other ways of finding interconnected and holistic truth. We need an interplay between available methods of exploration and discovery: respect for scientific endeavour and the many instances in which it is utterly vital, and receptive sensitivity to that lowest of all proofs ‘anecdotal evidence’ when it is harvested over years of earnest and honest observation, and corroborated across millennia. It is right and sensible to place an appropriate proportion of faith in science; but we must not forget to trust in the many-fathoms-deep wisdom of our bodies.

I love that science is translating areas of my yoga practice, but I find the parallels between my time zone corridors and the Tibetan ‘betweens’ particularly compelling, because these conclusions were reached with nothing other than time spent in silent contemplation. Individuals thousands of years apart, mapping little pockets of reality, soul cartographers creating our own maps that look spine-tinglingly similar. I can’t help but wonder whether the parallels I have uncovered between my experience of ‘life between’ and the Tibetans, would also exist in the intermediate states between death and rebirth. Why does the cycle of reincarnation feel like such an affront to our western way of thinking? Have you been there at the birth of a baby, and felt the strange otherworldly wisdom of lives already lived that seems to cling to them as they arrive in this life, a soul back from the between? Proclaiming faith in the idea of reincarnation is still too big a step for me to take. But I did feel those things when my daughter was born, and I think it is important to make a bit more space for these private, personal, impossible-to-quantify feelings.

There should not be a hierarchy between scientific experimentation and contemplative exploration; they are two very different lines of enquiry, each crucial in their own distinct ways. We will not find a vaccine for coronavirus by sitting in silent meditation. Neither are we likely to translate all of universal existence, using only the language of science. In researching dream theory and the science of sleep, I found myself submerged in an area where the scientific model has struggled; we do not yet ‘know’ conclusively why we dream or what dreams are, just as we do not yet know conclusively why we are alive, or what being alive actually is. To me these questions are simply too vast and soft-focus for how science works. I suppose that is why they have historically belonged to the territory of religion. But it is in these spaces between the clear-cut evidence that we must remember there is a depth of felt human experience that may help us circle ever closer to truth.

One Comment Add yours